Doobie No Harm

Doctors and the War on Drugs

Why is it that when you go to your doctor to ask about medical cannabis, or tell them about your medical usage, hoping to integrate it into your care, they don’t seem to know much about it? The sensible dictum to “discuss your medical cannabis use with your doctor” collides with the grim reality that when you do, it is rare that anything helpful occurs. At this point in history, most doctors are in favor of, or at least not opposed to, legal access to medicinal cannabis. But, as a profession, we know very little about it and aren’t good at discussing it with patients.

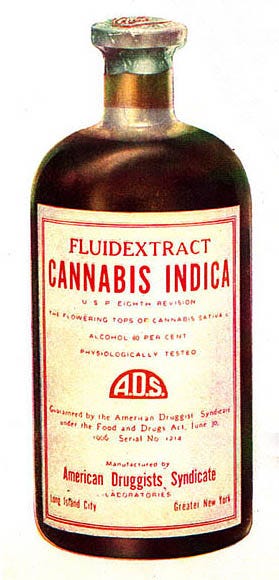

It wasn’t always so. Throughout the second half of the nineteenth century, right up until 1937, when cannabis became effectively prohibited in the United States by the Marihuana Tax Act, doctors routinely prescribed cannabis tinctures and considered it to be an effective, mainstream medicine. It wasn’t controversial. The American Medical Association, back when it was a helpful organization, testified against the criminalization of cannabis.

So how did American physicians go from being ardent proponents of, and experts in, cannabis medicine in the 1930s to their current black hole of knowledge about even the basics of medical cannabis?

The passage of the Marihuana Tax Act in 1937 made it virtually impossible to perform research or to treat patients with cannabis. Without lived experience, doctors and patients alike are susceptible to manipulation and propaganda. Harry Anslinger, the mercurial director of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, waged a campaign to force doctors into allegiance with the government’s hateful and restrictive position against cannabis. Anslinger, with the help of the Hearst newspaper empire, waged a decades long smear campaign against cannabis, exploiting racist tropes and irrational fears about Blacks and Mexicans.

In 1967, just thirty years after the American Medical Association (AMA) testified against criminalization before Congress, the AMA’s position, expressed in an editorial in the Journal of the American Medical Association, was that “cannabis (marihuana) has no known use in medical practice in most countries of the world, including the United States.” (Emphasis added. One must ask: in what countries does it have medical use? And why would it be useful there and not in the United States?)

The AMA goes on to state, “The use of marihuana among Puerto Ricans and both southern and northern Negroes is reputed to be quite high. In all likelihood, marihuana use among the poverty-stricken urbanite is concomitant with other dependence-inducing substances and a broad range of asocial and antisocial activity.”

The AMA, and many of their members, had clearly bought the propaganda campaign, hook, line, and sinker. The piece closes with a rousing call to action: “Marihuana is centuries old, but it represents a constant danger. The responsibilities of the citizen, including the physician, are clearly defined. The time to begin is now.”

The AMA hasn’t really changed its position much in the subsequent fifty-seven years. For example, in 2022 they decided to support expungements of cannabis-related offenses, so they can appear to not be completely out of touch with the racial justice movement. Yet, they remain opposed to cannabis legalization, so there will continue to be more cannabis-related offenses (that need to be expunged). In 2023, they state, “cannabis for medicinal use should not be legalized through the state legislative, ballot initiative, or referendum process.”

This suggests that they are OK with the fact that more than 20 million Americans, mostly with Black and Brown skin, have been arrested since the War on Drugs began for nonviolent possession of cannabis. These arrests have caused a profound amount of damage to families, and have greatly harmed employment prospects, education, and housing opportunities.

(As you are reading this, you might not be surprised that only 15–18 percent of American doctors currently belong to the AMA, down from 75 percent in the 1950s.)

Why on earth did the doctors of the time go along with this obviously contrived propaganda campaign? How did they end up on the wrong side of the War on Drugs?

This sea change in physician beliefs about cannabis was not driven by any legitimate or evidence-based discussions about health concerns. It was driven by external forces to which the doctors succumbed: racial, corporate, and sociopolitical. Doctors would come to parrot and amplify the U.S. government’s harmful (and largely untrue) claims about cannabis. If you repeat something enough times, it can start to become your truth. These vastly exaggerated beliefs became integrated into the accepted canon of modern medicine. One-sided medical research was funded, performed, and interpreted, in order to reinforce and amplify these beliefs. This isn’t to say that none of these concerns about cannabis had merit, but there was a very particular and one-sided context in which these concerns first arose, and became part of the mythology surrounding cannabis.

All along, there were a minority of doctors who stood up for honesty about cannabis and for not criminalizing the users of it. Generally, doctors, ever-present authority figures, were firmly placing themselves on the wrong side of the War on Drugs. One end result was the evolution of a profound rift, that we still see today, between the lived experience of patients who use medical cannabis and the accepted belief system of medical professionals.

By the time I started medical school at the Boston University School of Medicine in 1993, scientists were making one breathtaking discovery after another about the endocannabinoid system. However, scientific studies on the clinical use of cannabis still lagged far behind. My father’s then-new 1993 book Marihuana, the Forbidden Medicine was just coming out to great fanfare. In this book, my father explained,

The largely undeserved reputation of cannabis as a harmful recreational drug and the resulting legal restrictions have made medical use and research difficult. As a result, the medical community has become ignorant about cannabis and has been both a victim and an agent in the spread of misinformation and frightening myths. What follows is largely a book of stories because most of the evidence on marihuana’s medical properties is anecdotal. Someday the systematic neglect of the research community will be remedied and the authors of a book on the medical uses of marihuana will be able to review a large clinical literature.

Amen. I tried to do exactly that in my recent book, ‘Seeing Through the Smoke’.

I have always integrated medical cannabis into my own primary care practice. As with other medications, cannabis has side effects and toxicities to look out for. It doesn’t work for everyone who tries it. My rule of thumb is to ask, “Is this the least harmful treatment I could be using for this particular condition?” If the alternative is something like opioids or benzodiazepines (e.g., Valium), cannabis is usually safer. Cannabis has worked often enough, and well enough, to make it an indispensable tool in my toolbox.

The irony is that, as a primary care doctor, having medical cannabis as an option to help my patients actually makes my life a lot easier— and would do the same for other doctors if they took the time to learn about it.

For example, we don’t have an abundance of safe and effective medications for insomnia. First, one starts a patient on something that is supposedly relatively harmless like melatonin—though recently even this has been questioned. When that doesn’t work, to me it seems obviously safer to offer a few drops of a gentle CBD-predominant cannabis tincture (mostly CBD with just a little bit of THC, maybe a 4:1 or 12:1 ratio), which will allow patients to drift off to sleep in a mild, relaxed euphoria, than it would be to break out the heavy-duty tranquilizers such as Ambien or trazodone.

Similarly, for chronic pain, why slowly destroy the kidneys with daily NSAIDs if a modest dose of cannabis does the trick? (NSAIDS can also cause gastritis, bleeding, and heart attacks). Unlike traditional painkillers, cannabis can simultaneously alleviate four or five symptoms at once. For example, in a condition such as fibromyalgia, cannabis can help with pain control, negative perception of pain, insomnia, anxiety, quality of life.

There were reasons why doctors once used cannabis so widely and are starting to do so again—it works, and it is often a safer alternative.

Currently 94 percent of Americans support legal access to medical cannabis. It is difficult to think of anything else that 94 percent of Americans agree on. Doctors can no longer get away with shutting patients down with a pejorative, commanding, “You don’t use marijuana, do you?” (Of course not, doctor!).

Patients are hungering for high-quality information and are expecting their doctors to know enough about cannabis to have intelligent, helpful conversations about it. Cannabis-savvy patients aren’t inclined to give doctors the benefit of the doubt, perhaps knowing that cannabis has been legalized despite the doctors who (with certain notable exceptions) have been firmly ensconced on the wrong side of the War on Drugs. Most medical associations still weigh in on the wrong side of cannabis policy and have opposed virtually all of the state-by-state legalization initiatives. Most polls show that people would prefer to get accurate information about cannabis from their doctors than from anyone else, but that they don’t end up doing so. It’s time for doctors to get up to speed on this issue.

According to a 2017 study in the journal Drug and Alcohol Dependence titled, bluntly, “Physicians-in-Training Are Not Prepared to Prescribe Medical Marijuana,” it was documented that only 9 percent of medical schools have medical cannabis in their curriculum and that “84.9% reported receiving no education in medical school or residency on medical marijuana.”

Our “endocannabinoid system”—the vast network of neurotransmitters and receptors that controls a whole host of bodily functions and which also provides the mechanism by which cannabis acts—isn’t yet taught at most medical schools. This is astounding because this system is vitally important to virtually every internal system we have and mediates such essential functions as sleep, emotional processing, energy expenditure, appetite, and memory.

Even a doctor who thinks cannabis is the Devil’s Lettuce needs to understand the endocannabinoid system to be an effective doctor. If doctors haven’t been taught the basics of medical cannabis, and if they haven’t been taught the underlying physiology by which these basics would make sense, and if instead they have been subjected to a steady stream of misinformation, it is understandable that they wouldn’t be particularly open-minded about, and welcoming of, this field.

How can doctors get up to speed?

We need to be humble. To educate ourselves with a wide variety of resources. We need to be open to learning things we don’t know and to listening to the wisdom of other types of healers. We should be comfortable saying, “I don’t know—let me look it up,” or sending patients to someone who does know. Don’t bluff—that never turns out well. Don’t add to the stigma. Most of all, don’t shut down communication. There are many reasons why doctors and patients need to have open communication about cannabis, including side effects, anesthesia requirements, and potential drug-drug interactions.

That doesn’t mean you can’t express your opinion if you disagree; just do so respectfully and nonjudgmentally, so that you can keep the channels of dialogue open with patients. The way in which doctors embrace cannabis will be, in essence, a personality test for the entire profession. Can we muster the humility to learn this new field, to undo our past mistakes, and to help move the yardstick forward on social justice?

Meanwhile, what can patients do? Many patients have as bad a pot problem as doctors do, with the internalized stigma that has come from decades of Drug War propaganda and a lack of practical knowledge. The shame and self-doubting can be off the charts. I have had elderly patients slink into my office, check that the door is fully closed, look around as if to check that the shades are drawn, and then slyly whisper, “Doctor, I’m in pain, I can’t sleep. I can’t take Advil anymore because of my kidneys. Is it OK to . . . to try marijuana?”

Time slows. A dangerous pause. I wonder whether to wait for backup. I know my duty.

“That’s it, Grandma, on the floor. Right now! Hands where I can see them. I’m calling the DEA!”

I use my stethoscope to bind up the miscreant, press the panic button in my exam room so security will arrive, and move on to the next patient.

OK, not really. But the stigma is real, and sadly many patients are unnecessarily conflicted and feel needless guilt and concern. Over time, this stigma will continue to die down as millions of Americans are having positive experiences themselves—or with loved ones—using medical cannabis.

Patients must not let their doctors off the hook. Educate yourselves. Expect physicians to know a reasonable amount about this subject. Push back when we say things that aren’t true or that reek of paternalism, propaganda, or stigma. Bring us articles to read. Remember—with this issue, you have been leading, and we have been following. We screwed this up. We got it wrong. Our lack of both courage and independent thinking perpetuated the War on Drugs, which destroyed many families. Help us finally enter the twenty-first century on cannabis. While we are getting up to speed, as we start and reforming our conservative, mindless medical institutions on this issue, do your best to find credible sources of information that you can share with us.

It turns out that most doctors do believe that cannabis is an important medicine. According to a 2019 study, “A Survey of the Attitudes, Beliefs and Knowledge about Medical Cannabis among Primary Care Providers,” 58 percent of PCPs believe that medical cannabis is a legitimate medical therapy. Yet “one-half of providers were not ready to or did not want to answer patient questions about medical cannabis, and the majority of providers wanted to learn more about it.”

We are making progress. Doctors are slowly getting there. It will continue to take time to undo the unfathomable harm caused by our War on Drugs and the black hole of professional ignorance that resulted. At least we are heading in the right direction and, increasingly, doctors and patients will be on the same page about medical cannabis.

Amen! I’m fortunate to have a DO who was happy to prescribe cannabis for my chronic pain. Nothing else “pharmaceutical” was effective.

This was inspiring to read but also scary. There aren’t many choices of PCP who can handle someone who had your dad as a therapist while the manuscript was on his desk, let me know if you have any good ideas!! I remember how proud he already was, of his sons…