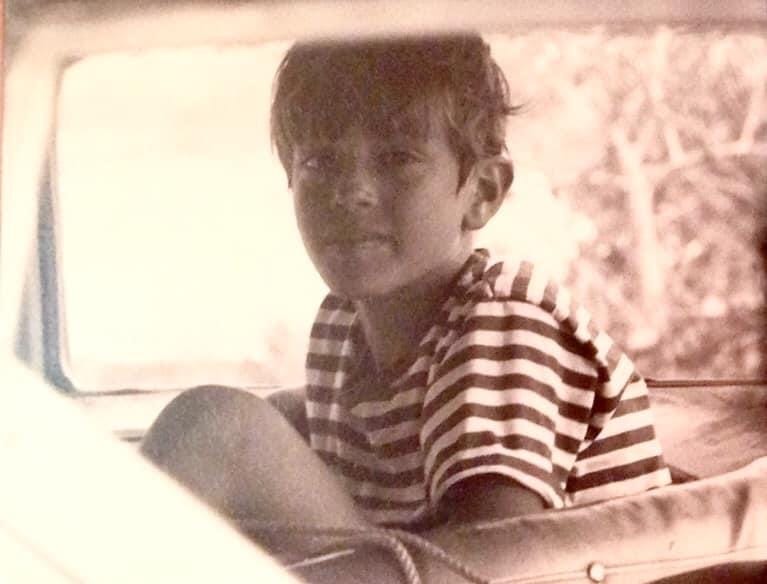

My brother Danny

How I learned as a child that medical cannabis is effective (and how I accidentally took my first puff when I was seven years old…)

It was 1973, two years after Nixon started his War on Drugs, when I first inhaled cannabis smoke. I was seven years old. I remember following my teenage brothers, Danny and David, as little brothers tend to do, like paparazzi, around our childhood home. Our parents were out, and they somehow thought the teenagers would responsibly supervise the younger siblings. Danny, fourteen at the time, casually pulled a thin white twig out of his pocket, lit it with a match in a practiced manner, and started sucking on the end of it, producing sickly sweet fumes. Normally an engaged and dedicated older brother, at this moment his teenage self must have assumed command because, with a mischievous grin, he handed me the white object and instructed me to put the tip into my mouth and breathe in, just as he had done. I would have jumped off a cliff if he had asked me to. I spent the next five minutes coughing and gagging as Danny went inside to get me a glass of water, clearly feeling guilty about his poorly thought-out prank.

Danny’s act of smoking a joint at age fourteen wasn’t as blatantly delinquent as it sounds, because cannabis was helping to sustain him. It was the only thing that allowed him to keep food down given the aggressive chemotherapy regimen he was on during his losing battle against acute lymphocytic leukemia. My parents, after quite a bit of soul searching— and then some actual cannabis searching—eventually sanctioned his usage. I believe that they knew by that point that he was dying, and they had decided to minimize his suffering at all costs.

This culminated in my law-abiding mother going to the athletic field next to the high school in our Boston suburb and asking Danny’s best friend, Mark, to sell her some weed. Mark was so shocked and worried he almost spontaneously combusted. “Oh, Mrs. Grinspoon, I wouldn’t know anything about that.” Mark’s loyalty as a friend and empathy for how sick Danny was must have won out over any fear of potential repercussions. Later that night, Danny announced to my mother, “Oh, Mom, guess what? I have a pipe with some grass in it in my jacket pocket.”

The use of cannabis may only have added months to a year to Danny’s life, but the improvement in his quality of life was incalculable. Instead of barfing, he was eating. Instead of lying in bed in a dark room, he was playing with his little brothers, inventing intricate board games, and strumming on his Fender Stratocaster.

It is true that, at the time cannabis was illegal, and it was front and center in the culture wars in Nixon’s America. If detected by the wrong people, my brother Danny and my parents could have been arrested. Their jobs as teacher and doctor could have been jeopardized. The medical establishment, which included my father, a Harvard psychiatrist, was, at that time, ideologically programmed to be opposed to any cannabis use. But when push comes to shove, most parents will do almost anything to help their children. This was a simple calculus: no cannabis, no appetite, no food, no Danny.

The healing power of cannabis became folkloric in my family. The lived experience of its powers to alleviate suffering, and to prolong and sustain life, was seared into my brain at an early age. I learned to associate the sweet smell of cannabis with healing. This insulated me, as the years went by, from the absolute nonsense of the DARE program. It carried through to a career in medicine and allowed me to see through the misinformation that they teach young doctors in medical school about cannabis. I am proud to say, largely due to Danny’s experience, that I have been treating patients successfully with medical cannabis, for twenty-five years.

Addendum

No one has told Danny’s story more eloquently and clearly than my father Dr. Lester Grinspoon, who was a legend in the psychiatric world and who was the intellectual lynchpin of the campaign to legalize medicinal marijuana. He first started this journey in 1971 when he published his masterpiece, ‘Marijuana Reconsidered’ which fundamentally shifted the national debate on cannabis, and shined a spotlight on how fundamentally ill-informed the U.S. medical establishment was on cannabis. In 1993, he wrote an equally important work, “Marihuana: the Forbidden Medicine”, which explained how and why cannabis worked to help millions of patients. It helped paved the way for California to legalize medical marijuana in 1996.

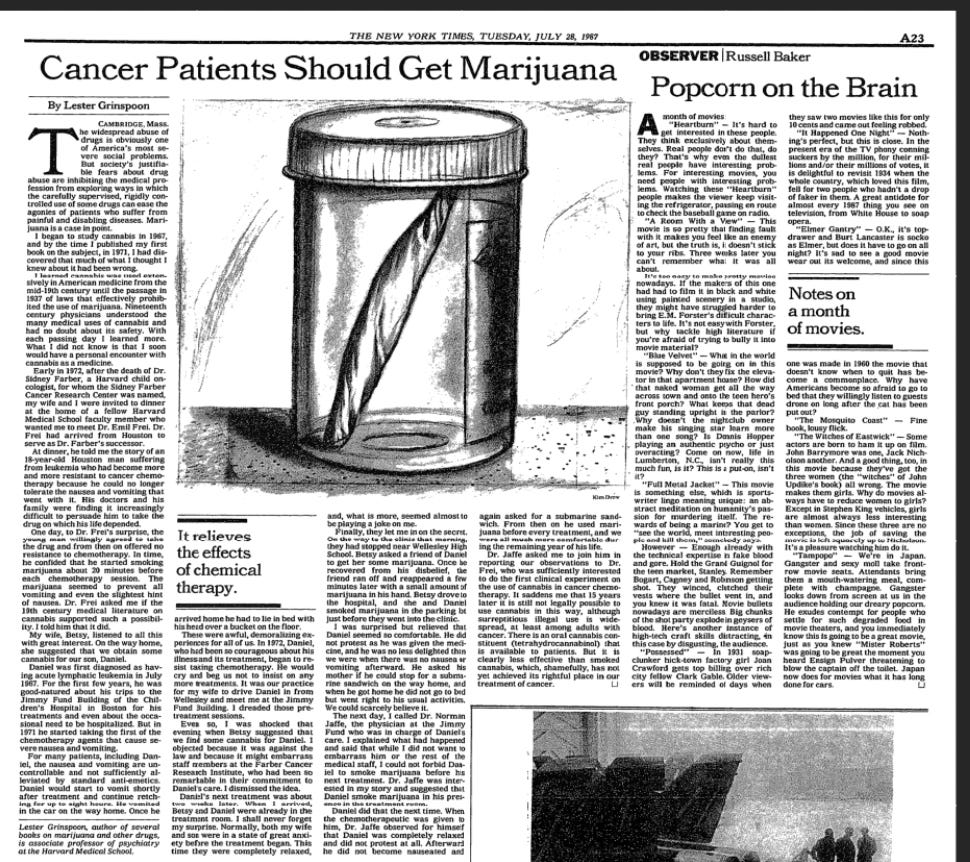

In a 1987 New York Times editorial, published at the height of Reagan’s catastrophic War on Drugs, my father told Danny’s story and made an eloquent pitch for allowing patients to use medical cannabis. This is a critical piece of intellectual history, a living testament to the power that one dedicated person has to nudge the world’s trajectory. I have included it below.

Cancer Patients Should Get Marijuana

The New York Times, July 28, 1987

Dr. Lester Grinspoon

The widespread abuse of drugs is obviously one of America’s most severe social problems. But society’s justifiable fears about drug abuse are inhibiting the medical profession from exploring ways in which the carefully supervised, rigidly controlled use of some drugs can ease the agonies of patients who suffer from painful and disabling diseases. Marijuana is a case in point.

I began to study cannabis in 1967, and by the time I published my first book on the subject, in 1971, I had discovered that much of what I thought I knew about it had been wrong.

I learned cannabis was used extensively in American medicine from the mid-19th century until the passage in 1937 of laws that effectively prohibited the use of marijuana. Nineteenth century physicians understood the many medical uses of cannabis and had no doubt about its safety. With each passing day I learned more. What I did not know is that I soon would have a personal encounter with cannabis as a medicine.

Early in 1972, after the death of Dr. Sidney Farber, a Harvard child oncologist, for whom the Sidney Farber Cancer Research Center was named, my wife and I were invited to dinner at the home of a fellow Harvard Medical School faculty member who wanted me to meet Dr. Emil Frei. Dr. Frei had arrived from Houston to serve as Dr. Farber’s successor.

At dinner, he told me the story of an 18-year-old Houston man suffering from leukemia who had become more and more resistant to cancer chemotherapy because he could no longer tolerate the nausea and vomiting that went with it. His doctors and his family were finding it increasingly difficult to persuade him to take the drug on which his life depended.

One day, to Dr. Frei’s surprise, the young man willingly agreed to take the drug and from then on offered no resistance to chemotherapy. In time, he confided that he started smoking marijuana about 20 minutes before each chemotherapy session. The marijuana seemed to prevent all vomiting and even the slightest hint of nausea. Dr. Frei asked me if the 19th century medical literature on cannabis supported such a possibility. I told him that it did.

My wife, Betsy, listened to all this with great interest. On the way home, she suggested that we obtain some cannabis for our son, Daniel.

Daniel was first diagnosed as having acute lymphatic leukemia in July 1967. For the first few years, he was good-natured about his trips to the Jimmy Fund Building of the Children’s Hospital in Boston for his treatments and even about the occasional need to be hospitalized. But in 1971 he started taking the first of the chemotherapy agents that cause severe nausea and vomiting.

For many patients, including Daniel, the nausea and vomiting are uncontrollable and not sufficiently alleviated by standard anti-emetics. Daniel would start to vomit shortly after treatment and continue retching for up to eight hours. He vomited in the car on the way home. Once he arrived home he had to lie in bed with his head over a bucket on the floor.

These were awful, demoralizing experiences for all of us. In 1972, Daniel, who had been so courageous about his illness and its treatment, began to resist taking chemotherapy. He would cry and beg us not to insist on any more treatments. It was our practice for my wife to drive Daniel in from Wellesley and meet me at the Jimmy Fund Building. I dreaded those pre-treatment sessions.

Even so, I was shocked that evening when Betsy suggested that we find some cannabis for Daniel. I objected because it was against the law and because it might embarrass staff members at the Farber Cancer Research Institute, who had been so remarkable in their commitment to Daniel’s care. I dismissed the idea.

Daniel’s next treatment was about two weeks later. When I arrived, Betsy and Daniel were already in the treatment room. I shall never forget my surprise. Normally, both my wife and son were in a state of great anxiety before the treatment began. This time they were completely relaxed, and, what is more, seemed almost to be playing a joke on me.

Finally, they let me in on the secret. On the way to the clinic that morning, they had stopped near Wellesley High School. Betsy asked a friend of Daniel to get her some marijuana. Once he recovered from his disbelief, the friend ran off and reappeared a few minutes later with a small amount of marijuana in his hand. Betsy drove to the hospital, and she and Daniel smoked marijuana in the parking lot just before they went into the clinic.

I was surprised but relieved that Daniel seemed so comfortable. He did not protest as he was given the medicine, and he was no less delighted than we were when there was no nausea or vomiting afterward. He asked his mother if he could stop for a submarine sandwich on the way home, and when he got home he did not go to bed but went right to his usual activities. We could scarcely believe it. The next day, I called Dr. Norman Jaffe, the physician at the Jimmy Fund who was in charge of Daniel’s care. I explained what had happened and said that while I did not want to embarrass him or the rest of the medical staff, I could not forbid Daniel to smoke marijuana before his next treatment. Dr. Jaffe was interested in my story and suggested that Daniel smoke marijuana in his presence in the treatment room.

Daniel did that the next time. When the chemotherapeutic was given to him, Dr. Jaffe observed for himself that Daniel was completely relaxed and did not protest at all. Afterward he did not become nauseated and again asked for a submarine sandwich. From then on he used marijuana before every treatment, and we were all much more comfortable during the remaining year of his life.

Dr. Jaffe asked me to join him in reporting our observations to Dr. Frei, who was sufficiently interested to do the first clinical experiment on the use of cannabis in cancer chemotherapy. It saddens me that 15 years later it is still not legally possible to use cannabis in this way, although surreptitious illegal use is widespread, at least among adults with cancer. There is an oral cannabis constituent (tetrahydrocannabinol) that is available to patients. But it is clearly less effective than smoked cannabis, which, shamefully, has not yet achieved its rightful place in our treatment of cancer.

Very moving. Thank you for sharing. All I would add is my opinion that marijuana consumption need not be "carefully controlled". It grows in the ground, just like magic mushrooms, just like the ingredients that create alcohol. We need to stop giving our power to government and large corporations. And let the f*cking people out of jail who were imprisoned for its usage.

This is a reminder that medicine is ultimately about reducing suffering, not defending ideology. The human truth in this story is undeniable.