Pain Control After an Opioid Addiction

Don’t torture patients – treat their pain!

I am seventeen years in recovery from a vicious addiction to prescription painkillers. My cataclysmic downward spiral, as a heavily addicted doctor, and then my return to medical practice, is detailed in my memoir “Free Refills”. I walked into a common trap for physicians (and other healthcare providers), succumbing to stress and ready access to medications (the “Free Refills” doctors and nurses are continually exposed to…). I became hopelessly addicted to Percocet and Vicodin, which led me to such strong compulsions that I routinely broke the law and stole drugs (which I am not proud of but…this is pretty typically what addiction can do to even a nice, ethical person.). As with all addictions, it starts out fun, with bursts of euphoria, and quickly ends up utterly miserable and ruinous.

After a profoundly stressful visit to my primary care office by the State Police and the DEA, (“cut the crap doc – we know you’re writing bad scrips”), followed by three felony charges, being fingerprinted, two years of supervised probation, 90 mandatory days in a brain damagingly inane rehab, and losing my medical license for three years, as well a brutal divorce (from a very stressful person…), I finally clawed my way into a sustained recovery from addiction. I believe that, at heart, recovery involves getting one’s need met in healthy, sustainable ways so that the drugs don’t have any place to creep back into your life.

What if you need opioids after a surgery?

What if you need opioids after a surgery? This is one question that I was invariably asked by colleagues, friends, and family members: now that you are in recovery from opiates, what are you going to do when you are in a situation such as an accident or surgery, when you might need to take opiates again?

I used to blithely answer this question with platitudes about how strong my recovery is those days, and how I would thoughtfully cross that bridge when I came to it. I punted consideration of this difficult issue into some unknown future time. Unfortunately, that future has now come several times, with major surgeries requiring opioids. How did I cope? How did I avoid a return to the nihilistic emptiness of addiction?

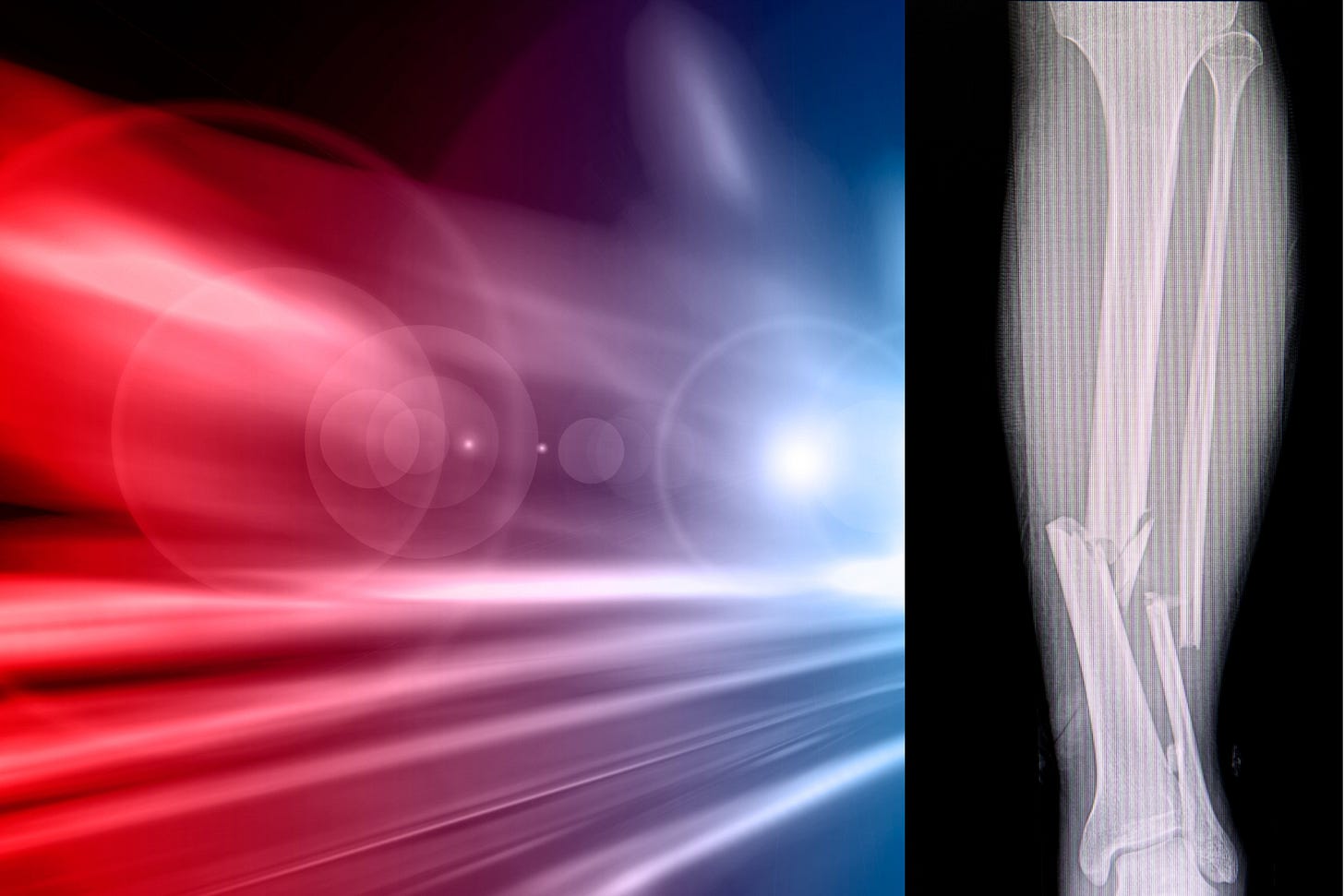

The most recent test was in August 2023 when I was mowed down by an elderly psychiatrist who was driving at night without her lights on. I was crossing the street with my family to get ice cream and she plowed right into me. I never saw her coming. My right leg was severely fractured. Lying in the road, I held my drooping foot onto my leg, to preserve the blood flow (and hopefully preserve my foot…) as the bones poked out of my leg.

Within minutes I was in an ambulance. They gave me 200ug of fentanyl – enough for 8 colonoscopies. It didn’t touch my pain at all, even in the slightest. It didn’t even make me sleepy which is amazing given that I hadn’t take opioids for years and had no tolerance.

I asked the medics for more, as the pain was all consuming, worse than I ever imagined was possible. They said, “you’re at the maximum dose, we give you more, you stop breathing.” At that moment, I was experiencing fentanyl-resistant pain.

The ambulance was headed to Man’s Greatest Hospital (MGH), the hospital where I work, and where I underwent a sequence of gruesome surgeries and painful procedures. Even on a good day, being in the hospital is excruciating, with procedures, blood draws, transfusions, I.V.’s, beeping machines that keep you up at night, moaning roommates, and pressing logistical issues like, ‘how am I going to get to the bathroom?”

What is a person who used to suffer from a substance use disorder (SUD) to do when they need pain meds?

There are tens of millions of us in this country alone who are in recovery from addiction, or who are suffering from an active addiction.

The reflexive response to this dilemma by many doctors is to minimize or withhold pain medications for fear of triggering a relapse. This might be logical on one level, but the problem is…this is inhumane and unethical. Pain traumatizes people and – believe me, they aren’t doing their patients any favors by withholding pain medications. In my experience, if you withhold pain control, people tend to seek out treatments on their own, which tend to be much more dangerous. For example, they buy pills on the street, which are often contaminated with fentanyl, which can lead to overdose.

The type of pain I experienced – pain from fractured bones or post-surgical pain – needs to be treated with skill and with empathy, and with adequately potent medication. Taking Tylenol or Motrin for this kind of pain is kind of like going after Godzilla with a Nerf gun. My leg was hurting beyond belief. I literally felt as if it were burning off. But - I had spent the last 17 years of my life conditioning myself, almost in a Clockwork Orange kind of way, to be aversive to taking any opioids due to the addiction.

Mindful opioid use

Fortunately, my doctors were enlightened about pain control and didn’t torture me in the hospital. I was kept reasonably comfortable. I was then sent home with a prescription for one of my previous drugs of choice: oxycodone. I am not, by any means, the first person who has confronted this issue.

There exist safeguards one can put in place if you have been addicted but need to take pain meds. It is helpful if you have a significant other or partner at home who can help manage the pills for you, and dole out two of them every four to six hours as directed, to avoid the temptation to take more than prescribed - in order to get high. Old habits die hard. I didn’t actually need to rely on this but was glad that I could put it into place if necessary.

It is important that you tell all of your doctors about your history of addiction. Not mentioning it is tempting specifically because some doctors might treat you more poorly if they know about an addiction due to their stigma and ignorance. It is still safer for them to know about a past drug problem so they can help monitor the situation and can help avoid dangerous drug interactions. In truth, the key to all addiction treatment is being open and honest. It is critical to check in with one’s entire support network about medications, cravings, and fears, and to use all of the recovery tools that are available to you. These include asking for help if you need to, being honest with yourself about how you are feeling, and not trying to control things that can’t be controlled. We don’t recover in a vacuum, but rather with our community supporting us.

In the end, my level of pain was so great that there really wasn’t any choice but to take the oxy at home, for several weeks. My nerve receptors were screaming in pain and they, in effect, made the decision for me. I’m sure there are Shaolin monks somewhere who can block out high levels of pain, but that just isn’t me.

I was reassured, and even pleasantly surprised, by several aspects of having taken the oxycodone. First, it worked well for the pain, gave me some desperately needed relief, and allowed me to get some sleep. Second, I did not get high from the pills. I guess that taking two pills is different from snorting five or 15, as we tend to do when we are addicted. Finally, it was very easy to stop taking them, and I have had absolutely no cravings or dreams about using since stopping. (When I originally quit, the dreams were brutal, and I would wake up in a cold sweat feeling guilty for having used.)

Critically, it is cruel and inhumane to not sufficiently treat any patient’s pain, especially after surgery. It is against our oath as doctors. We must not discriminate against people with substance use disorders. The millions of people in recovery from opioids are as deserving of pain control as anyone else. Doctors are urgently in need of education around this issue, as well as about how addiction is best conceptualized as a disease, not a moral failing or a deliberate choice.

I am grateful beyond belief to have survived my opioid addiction, and to not have become one of those common overdose stories we all read about in the newspapers. During my addiction, I came close a few times. I am also grateful to my excellent doctors at MGH for fixing my wounded knee, and for providing me adequate pain control. Fortunately, my recovery and my pain control do not seem to have been mutually exclusive.

A couple of final points. Medical cannabis was critical to my recovery and helped me transition more quickly off the opioids, which lessened my risk of a relapse of my addiction. This should be part of mainstream care. One day it will be, as physicians slowly get up to speed on this issue and catch up with their patients. Secondly, I wonder if the fact that I was on Wegovy (semaglutide) at the time helped lessen my cravings for opioids when I had to take them for pain. There is increasing evidence that this group of weight loss drugs can help with cravings and other aspects of addiction.

You are absolutely right about the PTSD from under-treated pain. I experienced classic PTSD symptoms after a myomectomy. Upon being hospitalized, the treatment team insisted that the "dynamics of the anesthesia" were the cause of the trauma. I was also surprised and disappointed that the postoperative pain relief was only twelve tablets of Tylenol #3. I attributed this to the fact that the intern who issued the prescription at time of discharge after surgery was MALE, and probably thought pelvic pain is supposed to occur, anyway. In other words, women in pain are no big deal. Or, at least this is the impression he left me.

What a well-reasoned and personal piece Peter. Kudos to you for successfully getting through that accident and then helping others.

Patty Straus